|

| image: the Heart Research Institute |

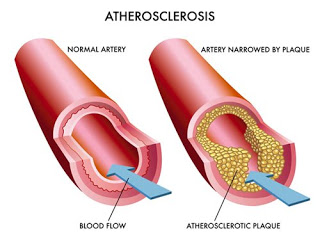

As such, think of this post less as the fifth installment in the series and more as part IIIb, as we'll be addressing basically what we talked about in part III (and touched on briefly in part IV). Let's recap some of the main points from that post. The coronary arteries are blood vessels that carry blood to the heart muscle, supplying that muscle with the oxygen needed to carry out its function--namely, pumping blood throughout the body. Blood flow through these blood vessels can be compromised by a disease process called arteriosclerosis--literally, a hardening of the arteries. Generally, arteriosclerosis is caused by the accumulation of plaques within the walls of the arteries, resulting in a narrowing/hardening of the arteries (stenosis) that can impede the flow of blood to the heart muscle. In times of increased stress on the heart (i.e., exercise), the demands of the heart muscle for oxygen are increased; if not enough blood is able to flow through these narrow, stenotic arteries to meet this demand, the heart muscle suffers from ischemia (lack of oxygen). Prolonged ischemia, or complete occlusion of the artery, can lead to infarction, or death of a part of the heart muscle--which, if significant enough, can be debilitating or fatal.

Remember that in part III, we discussed the use of CT scans in detecting underlying coronary artery disease--namely, looking for calcium deposition in the coronary arteries. Calcium is a component of many arterial plaques and is easily visible on high-resolution CT scans. This test is especially useful in folks who don't have any symptoms of coronary disease but may have risk factors. A growing body of research indicates that long-term endurance athletes--those who have been training at high levels or volumes for a decade or more--paradoxically have higher rates of coronary calcification than those of their age-matched peers in the general population, despite having much lower rates of many risk factors, like diabetes, hypertension, or obesity. Remember that these studies have demonstrated correlation, not causation--we can't say that sustained exercise is the cause of this finding, only note that the relationship exists. And recall also that we've yet to demonstrate what the real-world implications of these findings are--which is the point of this more involved discussion. To wit, the question: does having more coronary calcification lead to a higher risk of having a cardiac event? The short answer is, yes--but for marathon runners, maybe not.

Numerous studies of the general population (that is to say, not specifically among marathon/ultramarathon runners) have correlated coronary artery calcification (CAC) scores to a higher risk of suffering a cardiac event, such as heart attack, death, or the need for revascularization (a re-opening of a blocked artery). The exact degree of risk varies by study, but ranges from a four-fold risk increase to a twenty-fold increase have been reported in studies of varying size and quality. Higher CAC scores are associated with a higher degree of risk, with significant risk increases generally seen with scores above 100 or 300 (zero is "normal").

OK, so that's bad. Higher scores are associated with higher risk, and we've demonstrated that "obsessive" runners have higher scores, on average, than the general population. That means our risk of suffering a significant cardiac event must be much higher, right? Well, not necessarily. First off, as I mentioned in the earlier post, there is research suggesting that long-term aerobic exercise leads to coronary arteries that have larger diameter, and have a greater ability to dilate. (The autopsy of seven-time Boston Marathon champion Clarence DeMar famously revealed that his coronary arteries were two to three times wider than average.) Secondly, to better understand our level of risk, we need to understand the nature of arterial plaque and the reasons one might suffer from a cardiac event.

Generally, narrowing of the coronary arteries, in and of itself, is unlikely to cause a cardiac event. The precipitating factor in a cardiac event is often the rupture of an arterial plaque. A piece of the plaque can break off and get carried "downstream" to a narrower part of the artery. If it gets lodged there, it can cause a complete occlusion of blood flow to an area of the heart muscle, resulting in a heart attack. So if we can identify which plaques are more susceptible to rupture, this will allow for a better stratification of risk.

Simply put, not all plaque is created equal. Arterial plaque is generally composed of various substances: fat, cholesterol, calcium, and fibrin, to name a few. One way of thinking of plaques is to classify them as either "hard" or "soft". Hard plaque, made up of predominantly calcium, is generally considered more stable and less prone to rupture than softer (mostly cholesterol) or "mixed" plaque. The good news is that while high-volume exercisers have higher CAC scores, they are much more likely to have hard, calcific plaques (read: stable) and much less likely to have mixed plaques than subjects who exercised the least.

So while we know that elevated CAC scores in the general population put people at risk for cardiac events, the risk for runners who have elevated CAC scores may not be the same, because of the composition of their plaques, and possibly the dilation of their coronary arteries. Perhaps this is why, despite the fact that runners appear to have paradoxically higher-than-expected rates of calcification, cardiac events among habitual marathoners seem to remain relatively infrequent occurrences.